editing and "localizing" mediterranea inferno

I've been wanting to talk about Mediterranea Inferno's editing and localization process for a while. The problem with writing about editing is that I want to edit the fuck out of this, which doesn't help me finish it! This is a little long and meandering, half-diary and half-postmortem, but it feels appropriate; after all, I figured things out as I went when I was working on the game too. There's some strong language in this post, as well as spoilers for Mediterranea Inferno itself.

If you're unfamiliar: Mediterranea Inferno is a psychedelic horror visual novel by Milan-based solo developer Eyeguys / Lorenzo Redaelli. Three of the messiest young gay guys you've ever seen reunite after two years spent apart, with plans for an incredible summer vacation in southern Italy. A mysterious entity exploits their already-fragile friendship to turn them against one another in a battle royale where only the winner can ascend to Heaven. Mediterranea Inferno was nominated for the Nuovo Award and Seumas McNally Grand Prize at the 2024 Independent Games Festival, and won Excellence in Narrative.

The simplest way for me to describe my role in Mediterranea Inferno is "English localization editor". I say "localization" specifically, even though it might not be totally accurate, because it's the fastest way to convey that I didn't translate the game. The only Italian I can speak, I learned from Lorenzo, and it's probably not a good idea for me to repeat any of it here. Lorenzo (who also did all of the game's art and music) wrote the game's script in English — but English isn't Lorenzo's first language, Italian is. So the game's publisher, Santa Ragione, sought out an editor to help get the English script into better shape. That was me!

The first time we went through this was actually on Lorenzo's first game, Milky Way Prince, which is a semi-autobiographical visual novel following an abusive relationship. I was pretty nervous about the idea of doing it — I had edited a few game scripts by that point, but they were all written by native English speakers. I ran into lines in Milky Way Prince where I recognized every word in a sentence, but I had no idea what the sentence itself meant or was trying to say, and the idea of accidentally corrupting an artist's work because I couldn't understand their intended meaning was kind of horrifying! The semi-autobio nature of it added to my nervousness — what if something I thought was an innocuous editing suggestion was actually asking him to sand down a real-life experience he'd had? So I said I would only really feel comfortable taking the job if I could speak to the creator directly during the process, and Santa Ragione put us in touch.

(I'm glad every day that I took the job. Not because I loved the art, even though I did; I'm glad I took the job because Lorenzo is one of the coolest people I have ever met.)

When editing prose, I prefer reading a manuscript from cover-to-cover once before I really dive into working instead of making edits as I go. I take notes to capture my initial first impressions and reactions to things (necessary for me, but maybe not you — I have a terrible memory), but I'm not making big suggestions already. I like having a bigger picture of the work itself, as well as a solid handle on the author's voice.

When working with game scripts, I've been afforded the necessary time to do this exactly Never. I've had to get used to working as I go. I take extensive notes on my own first impressions and prefer working in formats where my edits aren't directly changing the script, so the writer has final say over everything. This usually even includes syntax changes — a comma added to a sentence, even if it's in a technically correct spot, can totally change how a line of dialogue reads in a visual novel. When I'm not working directly inside the original script, I can also quickly undo any proposed changes I've made if I need to. For example, if I've been saying Character A's dialogue sounds stilted or strange and proposing changes to make it sound more natural, and then I find out in the final act that Character A is an alien in disguise or something. Then I can find my suggestions and revise them instead of completely screwing up the original script.

It became apparent very quickly that I wasn't going to be able to do this for Milky Way Prince or Mediterranea Inferno. Almost every line in the script did need to be touched in some way. Mostly, it was a lot of smaller things like typos or grammar and syntax errors. It would've taken way too much time for Lorenzo to manually approve every single proposed change. He trusted me to handle these smaller changes, which I was really grateful for.

(Side note: something funny that came up both in the script and in Lorenzo and I's own communication is the way we both write out vocalizations in English. For a while I thought Lorenzo was fed the hell up with me because he prefaced a lot of his explanations or comments in response to my questions with "Uh,", which I initially read as a sort of… "Uh, I can't believe you're asking me this" or "Uh, is this not obvious?" And at some point I finally realized: "Oh, it's like when I preface my own explanations with 'oh'!" Little things like that can somehow change the entire tone of a sentence, which wasn't something I'd ever thought about before.)

For any bigger proposed changes, or places where I needed to ask for clarification because I was struggling to understand what a line meant, we had a shared document we both checked in on. I can't overstate how helpful Lorenzo was here. Whenever I asked for context about lines I had trouble parsing, he gave me extremely detailed answers. The most important thing is that he didn't just explain the literal meaning of the lines to me — he gave me insight into the feeling he wanted the lines to convey and what he was thinking about as he wrote them.

Lorenzo's writing immediately drew me in when I started reading Milky Way Prince. Even through any sort of language barrier, his writing bursts with intensity and emotion. The script didn't need perfect grammar for me to feel that intensity coming through; he writes so beautifully, from the heart, that it was impossible not to feel it as I read.

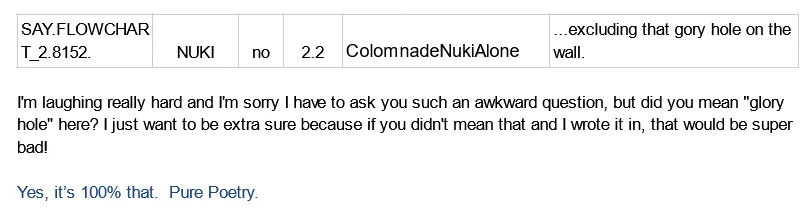

Also, one of the very first things I had to ask for clarification on was a typo of "glory hole", which was great for me to try to figure out how to phrase as professionally as I could within the first week of talking to a new client.

We settled into a good routine like this. And then I got really, really, really sick — to a point where I had to stop working on Milky Way Prince.

We worked things out (the last few chapters were completed by my husband, actually, who is also a wonderful writer and editor), but I was devastated. Not just devastated, but embarrassed — I felt like it was going to reflect horribly on me as a professional. Besides my apologies and telling him congratulations when the game launched, I didn't actually speak to Lorenzo again after that, despite how lovely he'd been to talk to while we were working together.

So it came as an enormous surprise when he and Santa Ragione asked me to work on Mediterranea Inferno a couple years later. Obviously, I agreed right away.

Mediterranea's first chapter was smooth sailing. I genuinely loved how raw and painful Milky Way Prince's writing was, but I noticed immediately that Lorenzo's voice as an author had become even more refined without losing that wonderfully raw honesty. In general, Mediterranea's editing process clicked for me much faster, partly because I'd had the experience from Milky Way Prince and partly because of the simple fact that I wasn't close to dying anymore. But then I hit a passage that needed way more involved changes than what I'd done on any project.

Mediterranea Inferno's story involves each of the three characters experiencing Mirages, hallucinatory mindscapes that are reflections of both how they see themselves and how they see the world. In these sequences, where the boys are separated from one another, they finally lay bare their innermost thoughts, desires, and vulnerabilities. So Mirages involve a lot of longer monologues and abstract, dreamlike writing.

The first one I encountered that needed reworking was this passage from one of Mida's Mirages. Mida is a model and influencer, simultaneously reveling in the love and attention he gets from fans while also being terrified of public scrutiny and his own deep insecurities. The entire sequence takes place submerged in a swimming pool. As Mida looks up from the bottom of the pool toward the assembled crowd on the surface, with the aquatic creatures swimming in the water above his head, this passage plays:

| Original Text |

|---|

| An indistinct mass who just get an indistinct image of me. |

| A muffled sound, incomprehensible. |

| I can't hear what they say, they can't hear what I'm saying. |

| They think they have idea of who I am. |

| But I choose what to show them. |

| I can hide, I can surprise them. |

| I'm in charge, this is power, this is control. |

| I'm their thalassophobia. |

| People love fear. |

| This is the only possible kind of relationship nowadays. |

| To not get hurt. |

Up until this point, Mida has seemed like nothing but a shallow, spoiled brat. He's haughty and catty, which has made him fun to read, but this is the first time we learn how he actually feels about anything significant. Reading this, I think you can see what I mean right away about Lorenzo's writing being evocative and intense. This passage jumped out at me immediately — it's beautiful, and I knew I had to make it shine the way it deserved. But I was struggling to do it with a light touch. Here's what I ended up proposing, and what made it into the final game:

| Revised, Final Text |

|---|

| An incomprehensible, garbled sound— |

| I can't hear their words, and they can't hear mine. |

| An indistinct mass gazes down at my shifting form below the waves. |

| They think they know who I am. |

| But I choose what to show them. |

| I can camouflage myself beneath the water. I can surprise them when I surface. |

| They only perceive me in the ways I want them to. {wi}In the ways I allow them to. |

| People love fear. |

| I'll be their thalassophobia. |

| This is it: {wi}the only possible way to be loved without getting hurt. |

(Note: {wi} is used when you want the player to click to advance the text without putting the text on a new line. Using these strategically in your visual novel is a great way to exert more control over the flow of passages.)

I tried to play up the aquatic language a little more — I wanted to evoke the imagery of Mida as some beautiful sea monster, something that can camouflage itself and wants to be both lovely and frightening at once. I also removed "This is power, this is control", because it was being said at a few other points during the Mirage and I didn't want them to lose their impact.

I've gotta be honest: I was fucking freaking out when I asked Lorenzo for feedback on this. I felt like… oh my god, these are rewrites, not edits. Am I going too far? Am I overstepping? Who the hell do I think I am, putting my hands all over this script?

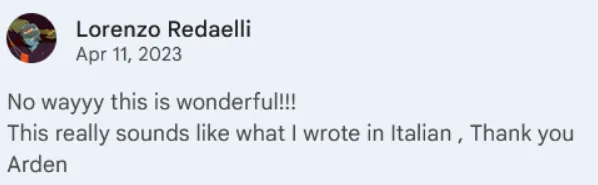

Lorenzo's response made the reality of my job finally click into place:

I am an American who only speaks one language. At the time of working on Mediterranea Inferno, I had never left North America, and I'd never traveled anywhere English wasn't the dominant language. Lorenzo constantly apologized to me for his bad English, and I constantly told him his English wasn't bad (because it isn't!). But because we'd been talking in English so effortlessly, it had NEVER occurred to me until this moment that there could be real, tangible differences between Lorenzo's story notes in Italian and his script in English, despite being written by the same person.

Because here's the thing: I said "so effortlessly", but it wasn't effortless for him! It was hard fucking work! I had never known the experience of wanting to express something but not having access to the right words. I'm ashamed it took me this long to realize it, but until this moment I truly hadn't understood the full extent of what writing an entire game script in your non-native language would mean for an artist.

So: it was not my job to make this script "easier for English speakers to understand". It was my job to bring the English script in line with the original Italian script. It was my job to help Lorenzo tell this story the way he would if he were a native English speaker.

(I only learned extremely recently that there is no "original Italian script" — the English version is the original script, and Lorenzo had been referring to his own private notes in his above comment. I still wanted to present my thoughts as I had them at the time to accurately reflect how I was approaching the experience and editing. The Italian script was translated directly from the final English version Lorenzo and I reached together by Claudia Molinari and Matteo Pozzi of We Are Muesli.)

Anyway, I assume every professional translator or localizer still reading this is rolling their eyes at me because yeah, duh. But it was both eye-opening and a massive confidence boost for me. I stopped feeling like a meddler putting my grubby hands all over someone else's art and moved forward feeling like I was actually helping.

(Another brief side note: I did finally travel outside of North America this year. On my first day in Tokyo after over 24 hours awake I almost had a nervous breakdown inside a Mister Donut because I promptly forgot every single word of travel Japanese I learned the second the cashier asked if I wanted a drink. Sorry, Lorenzo. I'm going to start learning Italian.)

I said that Mediterranea Inferno clicked faster for me, but it was also MUCH harder work. It is a game by an Italian, set in Italy, about Italian characters who are dealing with specific elements of Italian society and culture. I wanted to give the cast unique voices and manners of speech according to Lorenzo's guidelines while also making sure I wasn't making them sound like Americans.

Early on, I decided to use the Italian names of locations instead of English ones — Milano instead of Milan, Puglia instead of Apulia, etc. I also decided to leave specific Italian terms of endearment that the characters use for one another untranslated. The only real point where I wanted to use an English term instead of an Italian one was when it came to the nickname for the central characters. The trio are referred to in the Milan club scene as "I Ragazzi del Sole", which Lorenzo translated as "the Sun Guys". I specifically wanted the boys to only use the Italian name when they were talking about themselves or each other with genuine affection. They use the English name when they're being insincere or fake. Andrea, who is much more open with his emotions and affection, uses the Italian name more often than Claudio or Mida.

I learned a ton about Italian pop culture. For example, asking for clarification about this passage in Andrea's over-the-top campy beach Mirage:

| Original Text |

|---|

| It's not like I want to. |

| We all hurt each other, don't we? |

| The chances of killing are the same as being killed. |

| Isn't it the same for life? |

| We are called to, forced to do stuff, life is a mandatory conscription... to escape boredom. |

| You know... staying alone with your own thoughts... |

| It will be fun now! |

| Moreover, you know what they say about sailors! |

Led to Lorenzo telling me about Italian pop star Gianni Morandi and the film genre musicarello (he compared it to the musicals we had starring Elvis in the 50's) in addition to explaining Andrea's own feelings in the scene. With all of this context, we were able to go back and forth with simultaneous edits and localization, because I now had a much better understanding of the intended tone than a more bare-bones explanation would have provided.

| Revised, Final Text |

|---|

| It's not like I want to kill anyone, but… |

| We all hurt each other anyway, don't we? |

| In war, there's no way to avoid collateral damage. |

| Singing, dancing, killing, dying… It's all better than being bored. |

| We're conscripted from the moment we're born. We're all just good soldiers fighting the fight against ennui. |

| You know—that awful feeling when you're alone with your own thoughts? |

| But it's okay! I'm gonna have so much fun from now on! |

| And hey—you know what they say about sailors! |

I tried to play up the contrast between the character's frivolous, romantic tone and the dark subject matter. The entire Mirage has this aura of frantic desperation to it, revealing Andrea's desire to drown his social anxiety with sex, so I wanted to reflect that with this character brushing off the heavy topic at the end to move back into making raunchy, kind of antiquated jokes.

(This Mirage also forced Lorenzo to explain some dick jokes to me, which was another career highlight for me personally.)

I also ended up doing a lot of research into Italy's socioeconomic history, as well as delving deeper into how Mussolini's fascist regime shaped the country's culture in ways that still linger today. One of the final Mirages in the game directly evokes the imagery of Mussolini's balcony, and I genuinely lost sleep over trying to figure out how I could make the English text support such a bold visual choice. I'm putting this side-by-side, because it's quite a long passage:

| Original Text | Revised, Final Text |

|---|---|

| {b}Mida{/b}, contemporary martyr. | {b}Mida{/b}, our modern-day martyr. |

| Poor, unfortunate, debased boy. | Poor, unfortunate, debased child. |

| Looking for revenge. | So hellbent on revenge. |

| What a society you live in... | What a society you grew up in, hmm? |

| This might look like the future, but old-fashioned social paradigms haven't disappeared at all. | You know, this might look like the future, but the old social paradigms never really went out of fashion. |

| Inferiority complexes, the lust for payback and compensation are still here. | Inferiority complexes, the lust for payback and just desserts… |

| Insecurity, depression, anxiety still lead to the creation of emotional armor and the closure of emotional bonds. | Insecurity, depression, and anxiety—still forging armor to protect our emotions and blades to sever our bonds. |

| They fuel envy and lack of empathy. | We burn up empathy to fuel our envy. |

| On top of it all, the pandemic increased the distance between people—not only physically, but psychologically. | On top of it all, the pandemic increased the distance between people—not only physically, but psychologically. |

| We were angry, and now we're angry and afraid. | We were angry, and now we're angry and afraid. |

| Others became a threat—and don't even get me started on how individualistic and competitive our society is. | Now every body that isn't your own is a physical threat—as if our society isn't individualistic enough already! |

| Severing relationships and feelings, isolating and emotionally hibernating yourself... | Severing relationships, cutting off feelings, putting yourself in emotional isolation… |

| ...became a way to have more control over your and other's lives. | It's all a vain, scrambling attempt to keep some semblance of control over your own life. |

| You cancel, you block, you limit and you're scared other people will cancel, block or limit you. | You cancel, you block, you mute. Smash the faces off their statues so they can't tear yours down first. |

| Deep down, you know that's not the healthiest thing to do... | Deep down, you know it's not the healthiest way to live. Wouldn't it be so much better to trust one another? |

| Of course, it would be so much better to rely on each other... | But {wi}that's not possible. {wi}You've seen it yourself on this vacation, haven't you? |

| But it's not your fault. | People don't know any better. |

| We are continuously on display and exposed to others on social media. | We're all totally numb to one another. |

| We have internalized daily micro-dynamics of self-affirmation through mechanisms of real power. | We're all pretending to be the one true virtuous protagonist. {wi}But a protagonist needs an audience. |

| We pretend we're the "protagonists". | All media is meant to be consumed. You're already letting them peel and eat you, honey. |

| But it's always about an audience, it's always about others, and these things are slowly consuming you. | There's no way out for you. {wi}But you can still take control. {wi}You can show them the {i}right{/i} way to think. |

| But what can you do? That's the only way. | You're an influencer, {b}Mida.{/b} So influence them. |

You can see there's a pretty clear point where things diverge from the original. We felt like the original text was struggling to land because Madama was honestly making too much sense. In Lorenzo's words: Mida's idea of power isn't "I'm free to do what I want", it's "I can make other people do and think what I want". I wanted to bring that a little closer to the forefront of the text, because by this point the story has gone so far off the rails that we wanted things to be more campy and in-your-face. Madama is still speaking the truth, but now they're twisting it into the wrong conclusion: that the solution to all these problems is an ideology veering dangerously close to fascism, where Mida can and should force people to act and think just like him. Lorenzo and I were both really happy with how this turned out in the end.

There are a few other insights I'd like to share that I'm struggling to neatly fit into a post that's already too long. This is probably the closest I'm going to get to giving any actionable advice.

If you're a publisher in charge of getting a queer text localized or translated, do everything in your power to find a queer translator / localizer for each language. Early on in Mediterranea, when the guys meet up with one another, Andrea greets Claudio. After his initial hello, he originally said, referring to Claudio:

The fishiest queen of Italy.

In a queer context, "fishy" / "fish" is a term used to refer to a drag queen or trans woman who looks like a cisgender woman. It refers to the stereotype of vaginas smelling like fish. On a personal level, I fucking hate this term, but that's not what gave me pause when I read the line initially. It just didn't make any sense within the context of the scene. I told Lorenzo the meaning of it over here and asked if maybe there was a different meaning in Italy. Thank God I asked, because no, there isn't — he'd thought it was synonymous with "bitchy" and immediately asked if there was another word we could use instead.

I don't know if someone who wasn't queer would've caught this? They might've Googled it, seen it was gay slang, shrugged and then left it in. Or they might've assumed Andrea meant "fishy" as in suspicious. Either way — it would've left in a line that wasn't true to what the artist wanted at all, in two different directions! Not great!

So please hire and pay human translators, localizers, and editors; and try your hardest to hire people who have both the necessary skills and a familiarity with the subject matter of your script, whatever that may be. Nothing can respect and love the text and the author the way human translators, localizers, and editors can. All artists deserve to have their work treated with care.

My other obvious point of advice is this: if it is at all possible, facilitate communication between the original writer and a translator or localizer. I honestly have no idea how this works at bigger companies or for companies who specialize in this field; I can only speak to my limited experience in indie games with one publisher. I think it's become abundantly clear by this point exactly how much being able to talk to Lorenzo directly helped me work on the English script.

Part of facilitating that communication means allowing for extra time in the process, especially if you've got a significant time zone difference the way that Lorenzo and I do. I am incredibly grateful to Mediterranea Inferno's publisher, Santa Ragione, for being understanding and for allowing me the time I needed to do justice to such a beautiful script.

Lastly, I want to extend my deepest thanks to Lorenzo for allowing me to share his original English text for the purposes of writing this post, and I also want to thank him for being the biggest cheerleader I could've ever had about my own work on Mediterranea Inferno. You're an incredible artist, and I'm so lucky to get to call you a friend. I can't wait to see what you'll do next.